Nathan Stubblefield

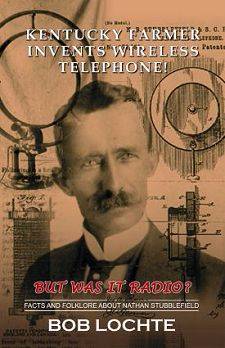

Kentucky Farmer Invents Wireless Telephone! But was it Radio? Facts and Folklore about Nathan Stubblefield by Bob Lochte

Around Murray, Kentucky, folks say he created radio. For nearly 70 years, they claimed that Nathan Stubblefield's invention made Murray the true "Birthplace of Radio." Elsewhere, people are skeptical. Read the story of what Nathan Stubblefield really did and how he became a folk hero — then decide for yourself.

"I have solved the problem of telephoning without wires through the earth as Signor Marconi has of sending signals through space." Nathan Stubblefield, 1902

To purchase the book, please call 270.809.3987.

About the Author

Bob Lochte is a Professor in the Department of Journalism and Mass Communications

at Murray State University in Murray, Kentucky, where he has worked since 1988. He

is a graduate of Bowdoin College, Columbia College - Los Angeles, and of the University

of Tennessee - Knoxville where he received his Ph.D. in 1987.

Bob Lochte is a Professor in the Department of Journalism and Mass Communications

at Murray State University in Murray, Kentucky, where he has worked since 1988. He

is a graduate of Bowdoin College, Columbia College - Los Angeles, and of the University

of Tennessee - Knoxville where he received his Ph.D. in 1987.

Previously, Dr. Lochte worked for 22 years in radio and television, beginning with a part-time job for WKDA-AM, Nashville, Tennessee, when he was in high school. Over the years he has worked in commercial and non-commercial broadcasting, cable television, and has owned and operated both radio and television stations.

Since 1990, Dr. Lochte has been learning about Nathan Stubblefield and other wireless inventors of the late 19th century. Over that time, he has published articles in both academic and popular periodicals including The Journal of Radio Studies, Timeline, Inc. Technology, and American Heritage of Invention and Technology. He has twice won awards from the Broadcast Education Association for excellence in historical research. In 1999, Dr. Lochte received a fellowship from the National Museum of American History at the Smithsonian Institution to study American wireless inventors and their work.

Reviews

I've been waiting for this one since first hearing about the featured inventor way back in graduate school more than 35 years ago. It's surprising nobody has done this before. But this appears to be the first book-length treatment on Nathan Beverly Stubblefield (1860-1928), the legendary Kentucky melon farmer who some (who don't know better) think invented radio years before Marconi. A member of the Murray State University faculty, Lochte has gotten behind years of local community hype to find out just what the man did-and did not-accomplish in a series of 1890s and early 1900s demonstrations.

What makes this self-published volume so useful is that Lochte has gathered more photos, patent reprints, and other information in one place than anybody else has managed over the years. While his findings won't please some of the Murray Chamber of Commerce types (who love to tout their town as the real birthplace of radio), they surely do place Stubblefield where he belongs-as an early telephone entrepreneur who pursued what turned out to be a wireless dead end. While purists might argue with Lochte's reference to his subject as "Nathan" throughout (they obviously did not know one another), that is a minor complaint for what is really a very well done biographical survey separating a bit of wheat from years of chaff.

Appendices include reproductions of Stubblefield's four patents, his 1902 statement on wireless telephony, a reprint of a 1902 Scientific American article, and reprints of an oft-cited speech and article on which others have drawn. Photos include both historical and current material and are well reproduced. This is fascinating and readable stuff.

It's the eyes - the windows of the soul - that first attract the reader to open this book. Nathan Stubblefield's eyes stare from the vintage photo on the cover, inviting a curiosity about an early age in broadcast history. Was Stubblefield a visionary Kentucky farmer who invented the wireless telephone, as the title declares? "But was it radio?" the subtitle taunts. No matter what, those very eyes were eaten out by a cat before Stubblefield's decomposing body was found after the hermit starved to death. This fascinating book sorts out the facts from the folklore surrounding Stubblefield.

This richly illustrated book is a lively mixture of odd truths to help both the curious reader and the competent historian. What is found in the book is a compelling tale that is really two tales. First, there is the story of Stubblefield's inventions: What they did, how they worked, and why they failed. And second, the reader sees how newspaper accounts combined with boosterism from his hometown chamber of commerce - complete with songs and plays - and theatrics from a wacky relative, created a fictional, almost mythical image of the man.

Beyond providing interest for the broadcast historian and radio buff, this book makes a distinct contribution to the history of media product marketing. For public relations and strategic marketing scholars, it traces in detail how the press can interplay with paid advertising and staged media events to promote a new technology. In Stubblefield's era, the inventor and his financial backers staged a press demonstration on the banks of the Potomac. Today, public relations firms vie for time on morning network news magazines to push hot new technologies.

This book is a delightful read.

The United States has its own homegrown Marconis, inventors who staked an early technological claim on ways of communication that dispensed with the annoying need for connecting wires. Amos Dolbear, Mahlon Loomis, and even Alexander Graham Bell all developed competing systems of wireless communication in the late nineteenth century that ran the gamut from the use of induction to light.

And then there is the case of Murray, Kentucky's favorite son, Nathan B. Stubblefield, an eccentric farmer and self-taught inventor who died in 1928. Legend has grown up around Stubblefield as the result of a series of inventions, experiments, and media coverage he received in his lifetime, as well as some outrageously self-serving claims made by others after his death.

Author Bob Lochte, a professor at Murray State University, has tackled head-on the messy tangle of truth and fiction that surrounds Stubblefield, and attempted to sort out just what's what. The first part of Kentucky Farmer... is a relatively brief factual account of Stubblefield's life and achievements. Ambitious beyond his rural farming background and self-educated about things electrical, Stubblefield made his debut in the fledgling telecommunications realm by supplying telephone services - of a sort - to his neighbors in Murray in the 1880s. His "Vibrating Telephone" was little more than a slightly sophisticated variation on the child's toy of tin cans connected to one another by a taut string. But at a time when Bell's telephone system hadn't yet spread to more rural parts of the country, Stubblefield sold enough of his contraptions to make a living from them for a time.

But the cause of all the controversy that exists to this day has to do with Stubblefield's invention of what amounted to a wireless telephone system that operated via earth conduction using rods inserted into the ground, a device he publicly demonstrated in Washington, Philadelphia, and (unsuccessfully) New York City in 1902. Stubblefield received much media coverage over the system, but Lochte reminds us that others had trod this path before; both William Preece and A. Frederick Collins, for instance, had previously invented (and patented) similar systems to Stubblefield's. At a time when a number of other early wireless pioneers (Lee de Forest pre-eminent among them) willingly engaged in shady stock promotions, Stubblefield, to his great credit, recoiled from the dubious dealings of a promoter with whom he had become involved. Abandoning his efforts to commercially market his earth conduction system of wireless telephony, and after failing to interest the world in an induction coil wireless system, he ended his life a secretive and desperately poor hermit living just outside of Murray.

It is here that the second part of Lochte's story begins: the construction of the mythology of Stubblefield as a misunderstood and neglected wireless genius, a process that began during his lifetime but which took off in earnest after his death from malnutrition in March of 1928. Journalists, the civic leaders of Murray, and even Kentucky State politicians relied heavily on gross exaggerations of a few facts and out and out untruths in their efforts to package and market Stubblefield. Enormous misunderstandings arose, for instance, over the fact that, since Stubblefield's earth conduction system employed telephony rather than telegraphy, it must therefore have amounted to the invention of radio. Accordingly, the community of Murray began to heavily identify itself as the "birthplace of radio." Lochte's account of the entire business makes for a fascinating case study in how legends and myths emerge from embellished truths and simple lies.

Bob Lochte has been studying Stubblefield and his legend since 1990. His research even led him and television engineer Larry Albert to build a working replica of Stubblefield's earth conduction telephone system and successfully demonstrate it. If anyone should get the Stubblefield story right, it should be him. And he doesn't disappoint. The thoroughness of his scholarship is evident throughout his book, and the inclusion of Stubblefield's patents in the appendices, as well as reprints of some of the period articles (including one from Scientific American) that helped get the whole Stubblefield myth started, are particularly useful for those who want to see exactly what the fuss has been all about and how it got started. At a time when Nathan Stubblefield's minor (but notable) achievements in early wireless communication have become so overblown as to rank him up there with Nikola Tesla in the eyes of many contemporary conspiracy theorists, Bob Lochte's Kentucky Farmer Invents Radio! proves to be a much-needed and welcome setting straight of the historical record.

Kentucky Farmer Invents Wireless Telephone: But Was It Radio? Facts and Folklore about Nathan Stubblefield appears to be the first book-length treatment on Nathan Beverly Stubblefield, the Kentucky farmer (1860-1928) who some think invented radio before Marconi. A member of the Murray State University faculty, Lochte has gotten behind the local community hype to find out just what the man did and did not accomplish in a series of 1890s and early 1900s demonstrations. Bottom line-Stubblefield did invent a type of conduction point-to-point wireless service, but it was most assuredly NOT broadcasting. What makes this volume so useful is that Lochte has gathered more photos, patent reprints, and other information in one place than anybody else has managed over the years. While his findings won't please some of the Murray Chamber of Commerce types (who love to tout their town as the real birthplace of radio), they surely do place Stubblefield where he belongs-as an early telephone entrepreneur who pursued a wireless dead end. While purists might argue with Lochte's reference to his subject as "Nathan" throughout (they obviously did not know one another), that is a minor complaint for what is really a very well done biographical survey separating wheat from chaff. The peak of Stubblefield's fame came in 1902 when his experiments were written up in several papers. But the story after that is all downhill...to his death from starvation in 1928. Lochte goes an important step further, however, and relates how the myths have grown since 1928, including reprints of oft-cited speeches and articles on which others have drawn. Fascinating stuff.

Murray State University professor Bob Lochte has separated fact from fiction in his book about Nathan Stubblefield, the Murray resident who many believe invented radio more than 100 years ago.

In Kentucky Farmer Invents Wireless Telephone? But Was It Radio? Facts and Folklore

about Nathan Stubblefield, Lochte has researched Stubblefield's somewhat eccentric

past, his claims about wireless signals, and how history got a little distorted through

the years.

While the book focuses on Stubblefield (Kentucky Monthly, October 1999, page 24),

it also presents a concise history of wireless communications.

Attempting to interpret the enigmatic mind of Nathan B. Stubblefield is almost certain to be fruitless but in his new book about the Calloway County genius/eccentric/fraud/recluse/legend, Dr. Bob Lochte discovers, speculates, and interprets more fully than any previous endeavor. He certainly is not the first to be so intrigued by the Stubblefield legend, but he is the first to produce a book which so thoroughly examines, and provides such an unprejudiced look at the life and life's work of this uneducated farmer who for a time captured the attention of much of the nation.

When a Murray youngster asked Dr. Bob Lochte if it was true that Nathan Stubblefield invented radio, he was speechless. After all the child had heard the lore that the Calloway County melon farmer had bested Guglielmo Marconi, and Murray was the self-proclaimed ”birthplace of radio.“

In 1892, Stubblefield created an electromagnetic induction wireless telephone and showed it to his friend Rainey T. Wells. The first words uttered over the device were ”Hello, Rainey.“

His curiosity piqued, Lochte ... sifted through collections at the Pogue Library and began piecing together Stubblefield’s life and ”the mind-set of 100 years ago.“

Lochte said: ”I don’t think it’s fair to evaluate old technology based on what we know today. People didn’t know that back then. You have to put Nathan into context. Really, most of the people who have found out stuff about Nathan haven’t done an adequate job.“

It’s obvious that a lot of folks want to know. They can start here, and if they want to know more, they can get the real documents and photos.

Ask anybody in Murray who really invented radio, and you’ll probably hear it was Nathan B. Stubblefield. But Bob Lochte says in his new book that Stubblefield’s inventions were not the forerunners of radio, an assertion that might seem like heresy in Murray.

Even so Stubblefield was not a failure. He did exactly what he intended all along - invent a wireless telephone system. ”Nathan apparently believed that wired telephone service wouldn’t come to rural America for a long time,“ Lochte said. ”He was right.“

Stubblefield showed his wireless telephone to Murray friends and relatives as early as 1892. Marconi sent the first long-distance telegraphic radio signal three years later.

Two stories are combined in the public’s knowledge of Stubblefield.

Stubblefield invented an acoustic telephone, which probably sounded better than the Bell phone. Once Stubblefield had established himself and was selling telephone systems as far away as Oregon and Washington, a group of doctors in Murray decided to purchase a Bell system, leaving him without a market. Undaunted, Stubblefield came out with a plan to develop a wireless telephone system, thinking if he did not have to run a wire, he could compete with the Bell system. Over the next 20 years, Stubblefield’s only focus was to develop and market a wireless telephone system.

A cousin, Vernon Stubblefield, who had taken care of Stubblefield during that last six years of his life, decided that he was going to connect Stubblefield with radio. At the same time, L.J. Hortin, a journalism professor at Murray State University, was setting up a lab to have student journalists cover events around Murray. Rainey T. Wells, the University President, and Vernon convinced Hortin that Stubblefield was indeed the inventor of radio. Thus began Hortin’s lifelong quest. Despite failed attempts to build a state park in honor of the inventor, he did coin the phrase ”Murray, Kentucky - The Birthplace of Radio,“ which could be seen on Chamber of Commerce campaigns until the early 1990’s.

According to legend, radio was created in Murray by Nathan B. Stubblefield in 1892. Unfortunately, this simple story has been corrupted and changed into the folklore it is today. Bob Lochte has recently written a book to clarify misconceptions about the life of Stubblefield and his involvement in the creation of a wireless telephone.

Lochte, because of his knowledge, received several calls a month from people who could not find all the information they wanted. ”It seemed to me that it would simplify things if folks had a book like this about Stubblefield.“ Lochte said.

For his book, Lochte spent many hours working with Larry Albert, WQTV engineer, collecting information from the Pogue Library and reading through files and folders stored in cardboard boxes. The two took the information and constructed a replica of Stubblefield’s model in 1992.

”We didn’t say whether it was a radio or not,“ Albert said. ”The book pretty much tells that.“

"Kentucky Farmer Invents Wireless Telephone!" was the resounding headline in the St. Louis Post Dispatch of January 12, 1902. The full-page feature went on to describe Nathan Stubblefield’s marvelous invention. Over the next six months, Stubblefield would demonstrate his wireless telephone at public venues in Washington, Philadelphia, and New York. It could even broadcast to multiple receivers simultaneously. Entrepreneurs created the Wireless Telephone Company of America based on his device. But Stubblefield fell out with his backers and lapsed into obscurity as rapidly as his star had risen. The most famous person ever to come from Murray, Kentucky, died of starvation, alone in a dirt floor shack.

A few months later, a young journalism professor and his students breathed new life into the Stubblefield story. With the encouragement of Stubblefield’s relatives and the president of the college, they disseminated the notion that Nathan’s invention was actually the earliest radio and that Murray was thus “the birthplace of radio.“ So began the legend of Nathan Stubblefield and more than a half century of promotion and boosterism associated with it.

In meticulous detail, Murray State University professor Bob Lochte tells both stories - the facts and the folklore - about Nathan Stubblefield. The text is richly illustrated with more than 50 original photographs from the Stubblefield collections at the Pogue Library and Wrather West Kentucky Museum. As an added bonus for scholars, Lochte has reprinted all of Stubblefield’s US patents and several historically significant documents related to his life and legend.